Shapes of Progress

In my last post I talked about the need, in context of organizational, commercial, and political decision making, to bracket out talk of Purpose and to focus on Progress instead. Defining your purpose is easier if it’s externally generated (like the military), but most organizations I work with have to generate it internally when they find that what purpose they started with has often long been accomplished. Ford is a great example, the masses already have affordable cars so now what? The trick is to not become a capital intensive financial institution. You can work to redefine a new purpose, but as addressed in the previous commentary, I think this is a dead end. Instead, it’s best to look at what you’re situated to do, what capability you have, and then make progress.

But the impediment to this is that one particular model of “Progress” at a macro level that transcends particular organization functions, and which bears the name itself, has been ideologically coded and made hegemonic such that diverse and alternate forms of progress are hardly seen as progress at all, and are largely considered deformations of the one true Progress. This is largely where the progressive - reactionary binary comes from, the appropriation of progress by a particular political ontology.

But ideological and externally motivated notions of progress resist metabolization. Hence the rise and inevitable hollowing out of ESG, DEI, or other social, and externally sourced, purposes which failed to be internalized to anyone’s satisfaction (advocates or shareholders). As a sort of inverted but otherwise parallel memetic rival to the military model (defining progress by way of adherence to an external, higher order purpose), it only works to the extent that the external structure subsidizes it. But it can never survive within an organization autopoietically. It creates a dependency and subordinates an organization to a function.

But there are alternative models. I’ll walk through some thoughts on what these models are, in hopes that we can resuscitate a notion of progress that widens the envelope of possibility. Then I’ll offer my perspective on which form represents the most viable direction for focus of this resuscitation, in hopes that once it’s named it’s usable.

So what is progress?

Let’s first map on dimension of progress as it relates to the end toward which something progresses. On one end you have a end goal that is defined a priori, and as such it takes the form of a representation. In other words, the end goal can be clearly imagined, articulated, and made visible. It is rendered as the end point. You can imagine that most construction and engineering projects share this feature, the future state is defined and representable in a drawing or blueprint. But when applied in social or political contexts, the more the end state is defined the more these projects tend toward utopianism, think Fordlandia. Ultimately, and catastrophically, such a representational mode of engineering applied to social contexts lands you at communism or fascism, in Voegelin’s terms, this would be the immanentization of the eschaton.

For people operating in business, design, or engineering, defining a goal and working towards it is unproblematic. We do it all the time, sketch a car, build it in CAD, engineer it…

But the more you zoom out, the more clearly see that to even build something like a car, you’re already making some larger systems level design decisions, such as building a car instead of light rail, or light rail instead of more densely integrated environments… And as you zoom out, the ability to totally represent and model the intended end state becomes much trickier, but people still try.

Communism and Fascist are examples par excellence, defined, respectively, by egalitarianism or an aesthetic national symbolization of order. As political ontologies, modern progressivism sits at the pole (the end being defined by equity and environmental equilibrium), as does popular conservatism (the end resembling a sort of revivified 1950s Americana). Again, Henry Ford’s Fordlandia sits here.) Let’s label this pole “Voluntary Purpose” because the end goal is volunteered (you provide it) and represented (it’s able to be imagined and articulated), it is defined and made into an image.

At the other end of this dimension, the opposite pole, we have an end state that is left open-ended or emergent. It resists definition or symbolization but is nonetheless a future state that marks progress. Consider evolution to be a clear example. Species adapt according to environmental conditions and become more or less fit, there is progression happening in the sense that there is movement toward fittedness but the end state of any species resists being able to be represented as such in advance. Information theoretic models of progress sit at this pole as well, progress may be defined by quantity of information or complexity but what that ultimately looks like isn’t symbolized imagistically. The process itself, it’s unfolding, is what defines progress and it doesn’t necessarily contain a normative dimension. Consider Berlin and Kay’s work on cross-cultural color terms, where social groups progress from fewer to more color terms as social complexity increases. Individuation is also an example here. This model of progress may be regarded normatively (as being more or less good) but it’s not necessarily required, one may hold that increases in complexity aren’t in fact good, but still recognize that the increase marks a type of progression. We can call this pole Ordained Purpose because the end state is revealed rather than modeled, inaccessible to human representation and definition. It’s unknown, whether it is providential or not doesn’t matter, what’s important is that the end state of this mode resists representation. (It’d be tempting to place more sophisticated forms of modern progressivism here, because of the assertion that diversity itself is an axiomatic good, except for the fact that diversity is ultimately rejectable when it doesn’t net out in accordance with the emancipatory project progressivism holds dear. Outcome dependence is antagonistic to emergence. This criterion is what places modern progressivism at the voluntary pole.)

And we can mark another dimension defined by the nature of the subject participating in each of these forms of progress. On one pole we have the subject (be they individual person, organism, or social group, it doesn’t matter) as Dispositional. This understanding of the subject entails that they come to be a subject with some durable, if not essential, pre-disposition. This could be a law-like orientation, set of tendencies, constitution, drives, historical enculturation, or something else, but at the abstract layer, they are decidedly not a blank slate. It’s easy to think through evolution, where animals have a nature. While the nature of a species may evolve through time, a given animal comes to the world pre-loaded with characteristics that constitute why the animal is that type of animal. At this pole, humans are conceived in the same way, they have a human nature (which could be universally encoded and/or culturally shaped). “Human nature” may even be an illusory effect of deep enculturation, but the very notion of enculturation at all assures disposition. People can debate on what that human nature entails, but at this pole, we agree that they have a nature and that that nature is a constraint. If you’re a commercial organization or a political entity and operate with this assumption, you build products and services that fit how you think people “are”. You don’t try to overcome cognitive biases, habits, enculturation, and tendencies, you work with them and leverage them to your advantage. An example of a product that does this is an internal combustion automobile in modern America. It assumes people have a set of behaviors, predisposed ideas of “freedom” and “individuality” and “ownership”, live a particular way, within a particular context, and build a product to serve that as is. It doesn’t matter whether these tendencies are “hardwired” or merely built up through enculturation or historical land use policy, the point here is that you work with what you have.

At the other pole, we understand the subject as able to be radically transformed. They may have a nature, but the constraints that nature implies are mere technical or cultural impediments which, with the right technologies, policies, or incentives can be negated or overcome. The subject is fundamentally a blank slate. Again, if you’re an organization operating at this pole, what you build or develop in some way looks to transform the given tendencies of your customer. Keeping the mobility example in modern America, this may be an electric vehicle or light rail service. Both entail transforming the subject in some way and proactively finding ways to change those given tendencies (could be as simple as converting refueling behavior to charging behavior). Notice that givenness here doesn’t need to be essentialist - there’s nothing about people in modern America that essentially predisposes them to a particular way of living- it’s just that those ways of living are durable enough that external incentive needs to accompany the product or service-offer to affect change. This is unlike the opposite pole for one crucial reason, for a subject that has a given nature, change is possible but comes by way of unblocking the fullest expression of their nature, their inherent latent potential. At this second pole, in contrast, change comes by way of external incentive, unblocking their path to transformation. The given subject’s givenness is not to be more realized but is, instead, to be transformed.

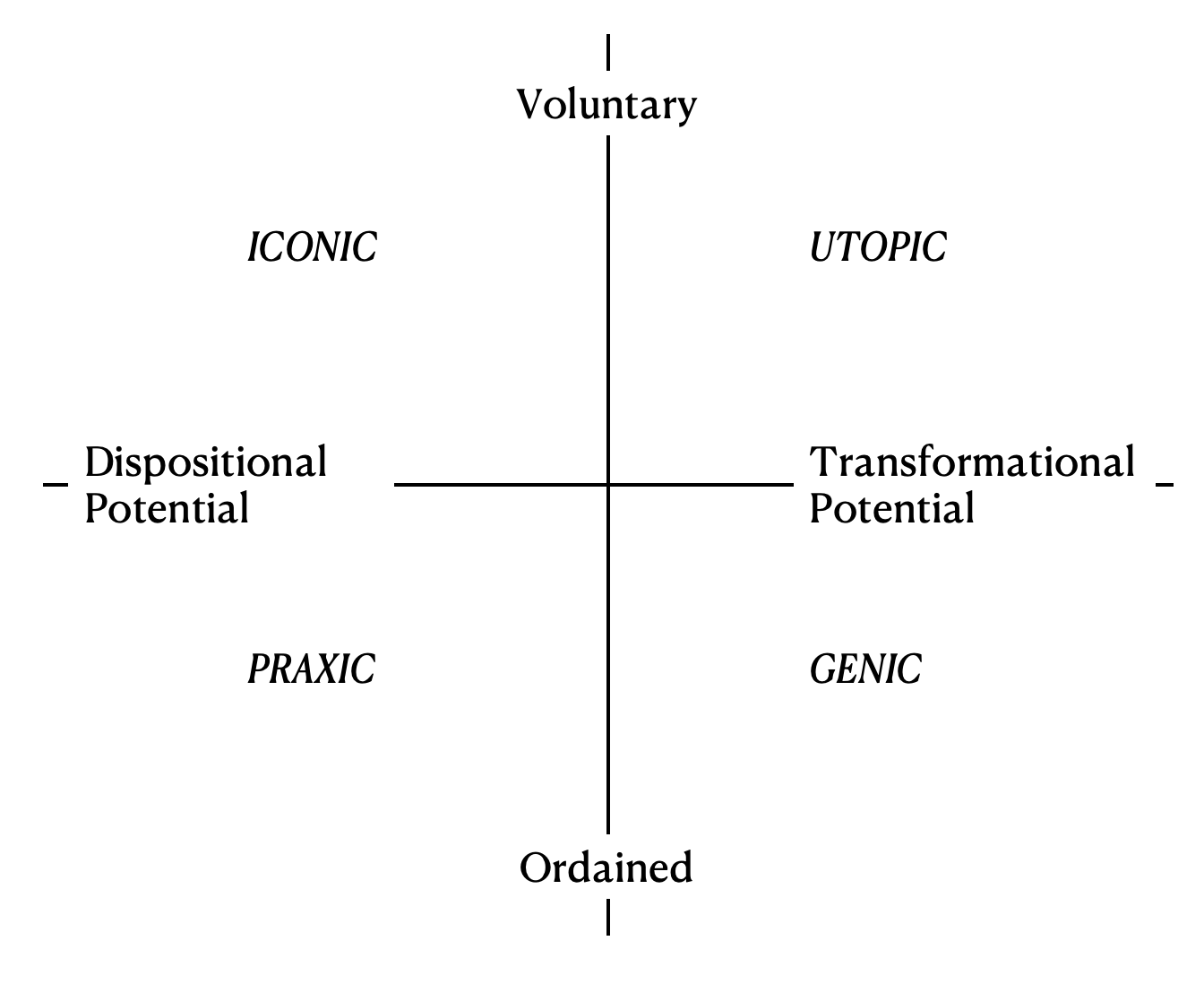

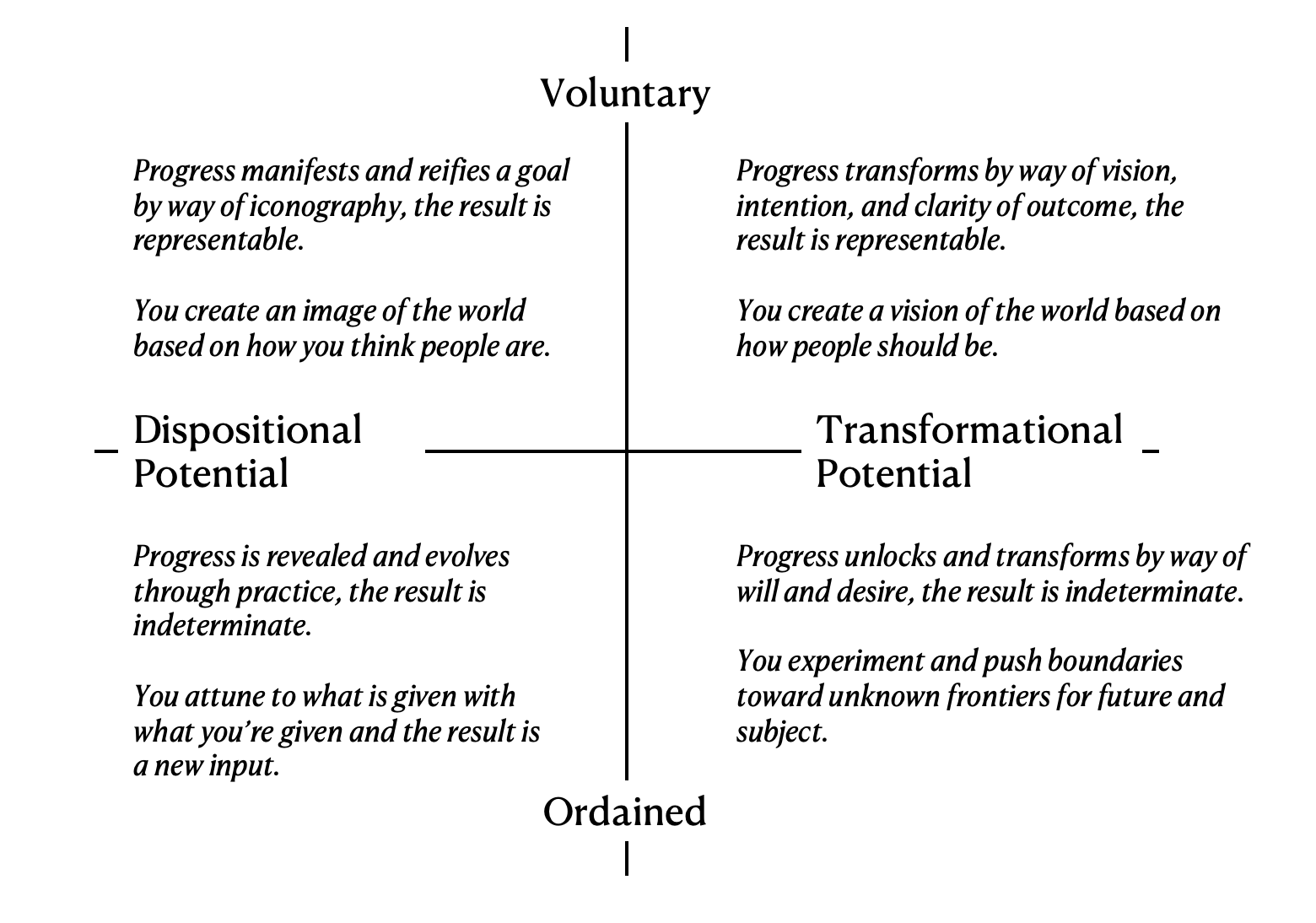

With these axes, as imperfect as they may be, you can make a map of the diverse expressions of progress relative to the ways they understand an end goal. Each quadrant is a model of progress combining two underlying assumptions: first, whether the end state is representable in advance or emerges (is revealed, only through unfolding); second, whether the subject is understood as possessing a durable nature (essentialist or not) or as raw material to be transformed.

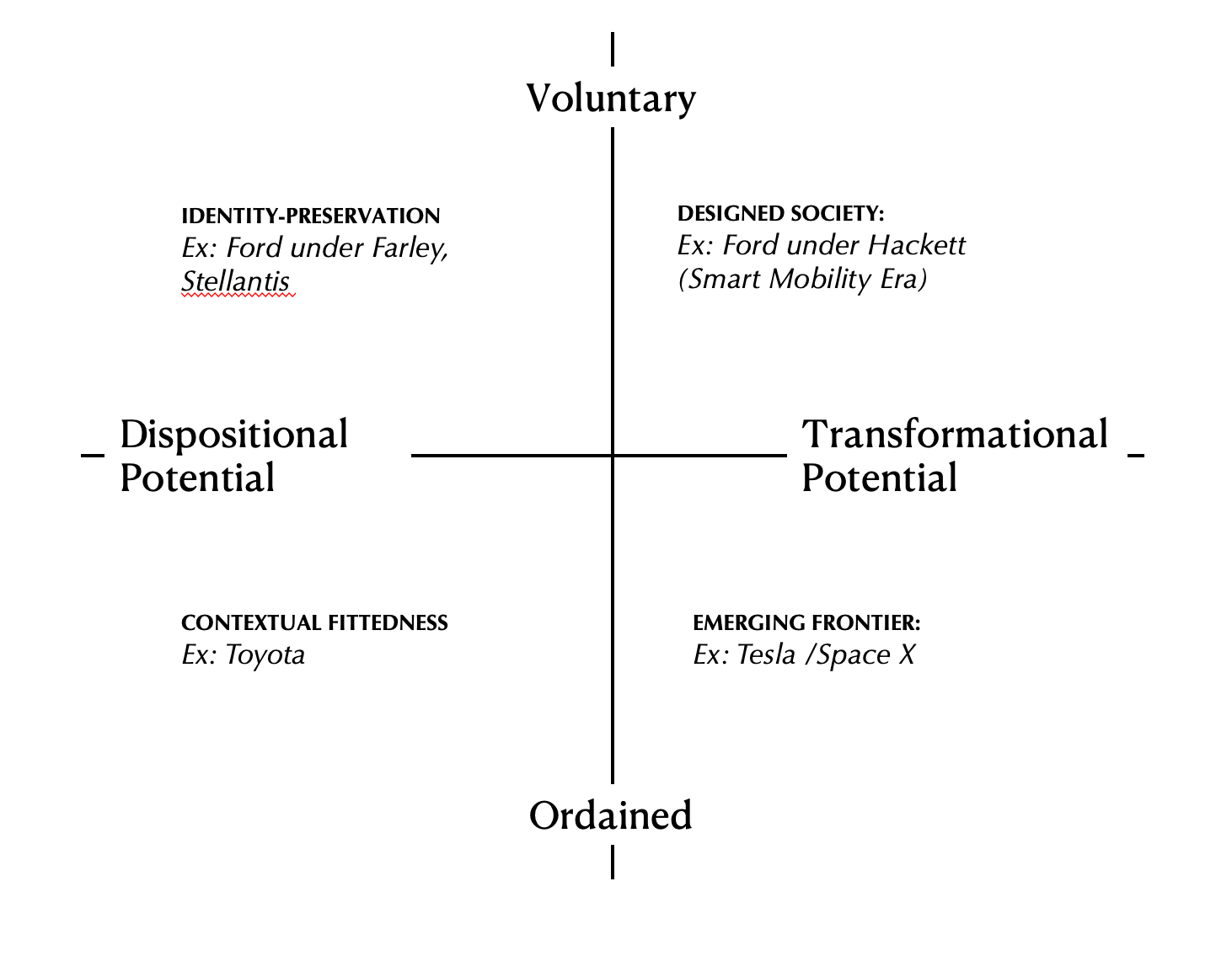

So now let’s zoom back in and look at an organization trying to understand what progress looks like. We can use mobility in Modern USA again as an example, and our map should help identify strategic orientations:

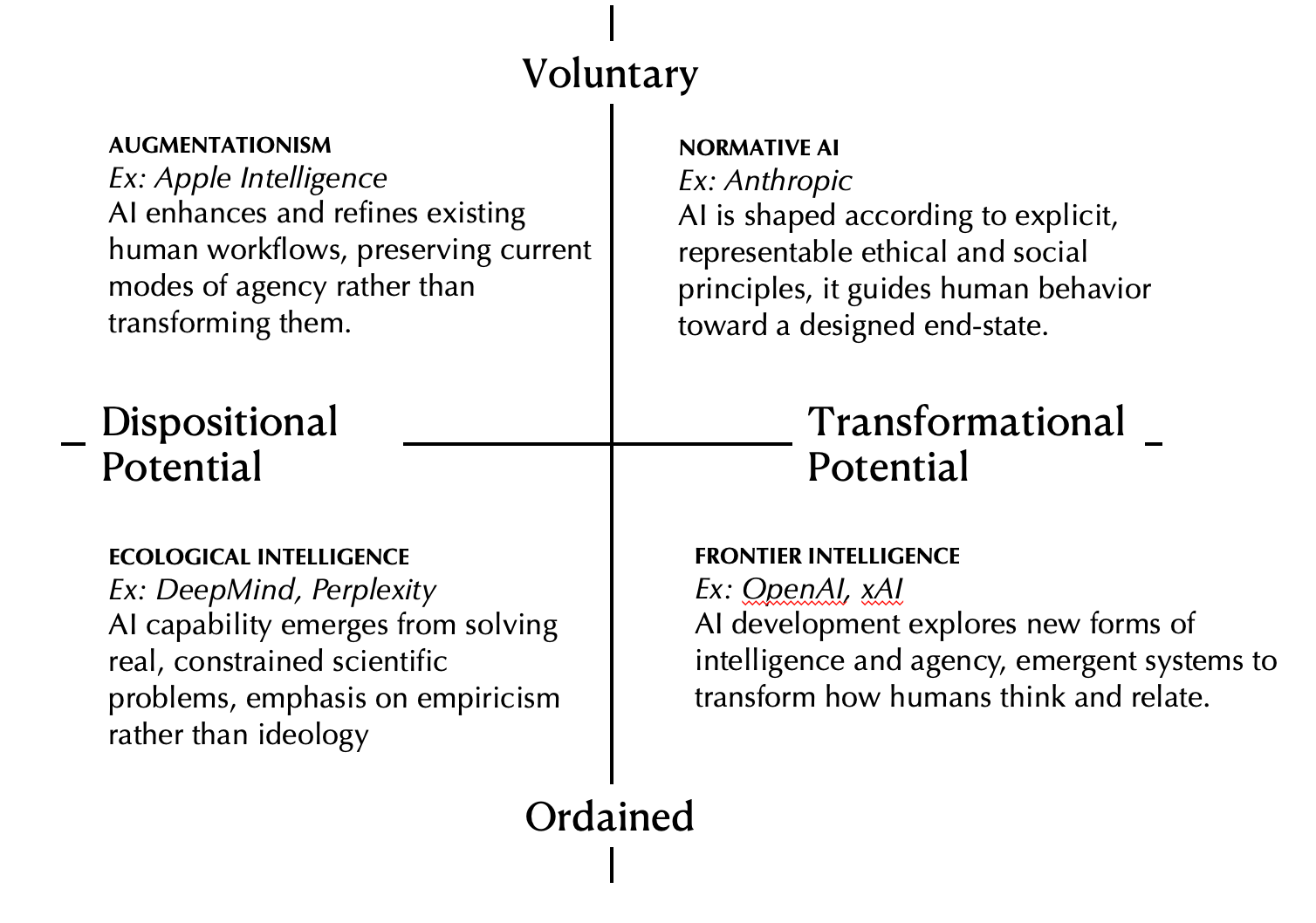

And we can map strategic developmental progress orientations for AI development as well:

Returning Vision Back to Index and Observation

So what are the models of progress here?

Upper Left: Iconic, progress is about achieving the vision of the better life.

Upper Right: Utopic, progress is about achieving the vision of the new life.

Lower Right: Genic, progress is about unlocking the possibility of new lives.

Lower Left: Praxic, progress is about unlocking the possibility of better lives.

Of course these are post-hoc placements, and you may not agree with the examples (I’m not even especially confident without more investigation, but take them as tentative illustrations), but if I were betting on long term viability or trying to steer development teams, I would be constantly checking in on the intuitive models of progress in play. In fact, I would redirect attention away from defining a purpose, or “finding your why”, and put much more attention toward observation (both internally and externally focused), using vision as an indexical tool (prototyping, experimentation, and deictic concepting) rather than as goal-articulation, and focus development of internal virtues rather than goal-alignment.

I’d place bets in, and steer teams toward, the lower left; redirecting Vision from something represented to something enacted through observation coupled with speculation. Right hand of the map is Quiet American territory. Top left contains progress with too limited a horizon, top right is all red flags (ideological fidelity cost, external dependency risk). Lower right is voracious.

My hope is that this map is useful for identifying hypotheses of strategic viability by way of interrogating an organization’s orientation to progress. And for organizations that are looking to set a course, to make the case that examining underlying assumptions about, and aligning on, what progress looks like is a more productive approach than codifying a purpose.